How new research is finally proving that a silent mouth doesn’t mean a silent mind.

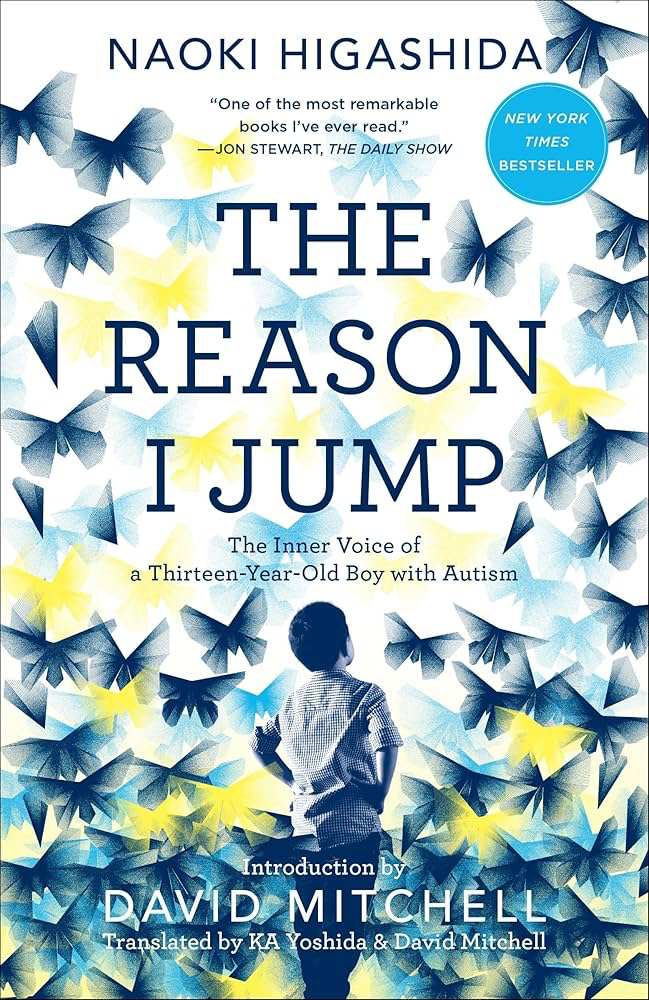

When I first read Naoki Higashida’s groundbreaking book, The Reason I Jump, it felt like a door opening into a world I thought was silent. As a thirteen-year-old non-speaking autistic boy, Higashida gave us a profound look into his inner life, and for anyone who works with or cares about autistic people, it felt essential. Yet, when I recommended it, I was met with a familiar, persistent scepticism. ‘They don’t speak,’ a friend once countered. ‘How do you know the words in the book are his? You just… trust it?’

Yes, I did. And it fundamentally changed my perspective.

A decade has passed. That friend and I have lost touch, but I finally have the answer I wish I could give them.

The answer comes from a recent UCL CRAE Annual Lecture (2025) by Professor Vikram Jaswal, a developmental psychologist whose work is scientifically validating what many of us felt intuitively: just because someone is silent doesn’t mean they have nothing to say.

Professor Jaswal and his collaborators set out to challenge the deeply ingrained assumption that non-speaking autistic individuals lack an interest in social interaction. His research shows the opposite. Non-speaking people want to communicate and socialise, but our methods have often failed them. He points to systems like PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System). Whilst useful, they can be limiting, as the vocabulary is chosen for the user, and communication rarely progresses beyond basic requests. Imagine wanting to tell a joke, share a fear, or debate philosophy, but your only tools are symbols of an apple and a toilet.

The core of the issue, Jaswal’s research reinforces, is often not cognitive but physical. Many non-speaking autistic people face immense motor planning challenges: difficulties in planning and executing the complex, intentional movements required for speech. It’s a physical inability to coordinate the hundreds of muscles needed to produce sound. It’s a ‘can’t,’ not a ‘won’t.’

This is also why the most insidious criticism, that non-speaking individuals who use a letterboard are merely being cued by their assistants, is so damaging. It’s a criticism born from a complex history of communication controversies, but one that Jaswal’s rigorous data helps to finally put to rest. It’s an accusation that dismisses not only their intellectual capabilities but their very agency. It’s a modern version of the old, ugly belief that a person with a different kind of body must also have a deficient mind.

Hearing a researcher of Jaswal’s stature systematically dismantle these biases was reassuring. I wasn’t alone in my belief. To prove it, his team designed several studies that treated non-speaking individuals as partners, not subjects. Their questions were direct:

1. Do non-speaking people have the agency to communicate for themselves?

To find out, the lab used eyetracking glasses on participants as they spelled on a letterboard. The critics’ ‘cueing’ theory would predict fumbling, slow, and random movements. The data showed the exact opposite. Participants were:

- accurate and fast: spelling at a fluid, rapid pace.

- strategic: their eyes darted to the next letter in a word long before their finger moved, proving they were planning ahead.

- pattern-recognising: they moved even faster when typing common letter pairings (like ‘th’ or ‘er’), demonstrating an internalised knowledge of language structure.

This wasn’t just abstract data. It was the mechanism for expressing deeply human thoughts with one young man in the study spelling out that he was ‘waiting for my dream girl’.

2. Can they convert sounds to letters—in other words, can they spell?

The team designed an ingenious task, like a game of ‘whack-a-mole’ on an iPad on a stand. Participants were asked to tap pulsing characters. Sometimes, they were told in advance they would be spelling a real sentence (‘I should water the backyard’). Other times, the characters were nonsense symbols. The result? People were significantly faster and more fluid when they knew they were spelling real words. They were anticipating the sequence which was a clear signature of literacy.

3. What does the future look like?

Jaswal left us with a tantalising glimpse into the future of using augmented reality (AR). Imagine a personalised communication interface, a bit like Iron Man’s Jarvis, projected into a user’s field of vision. AR is highly customisable and could be tailored to an individual’s unique motor and sensory needs, potentially offering a path to independent, private communication for those who can tolerate the headsets. The research is early, but the possibilities are thrilling.

As a teacher, these findings are more than just interesting; they are a call to action. They reinforce my belief in teaching every child literacy, phonics, and the rich world of language, because we simply do not know the depth of the minds we are engaging with. Who are we to decide what a child is capable of and, in doing so, deny them the opportunity to show us?

The guiding principle of the disability rights movement, ‘Nothing about us without us,’ is at the heart of this work. These projects show how essential it is to include people as experts in their own lives. I hope to see far more participatory research like this – research that doesn’t just study people, but empowers them.

References

- Higashida, N. (2013). The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism.

- Lecture: Jaswal, V. (2025, April 3). Supporting nonspeaking autistic people’s flourishing [Video]. CRAE Annual Lecture, UCL. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qnVs5u2S8bA